Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Powder Mater > Volume 32(6); 2025 > Article

-

Research Article

- A Self-Powered Cationic Microfiber-Based Triboelectric Air Filter for High-Speed Particulate Matter Removal and Smart Monitoring

-

Tae-hyung Kim2, Jin-Kyeom Kim1,*

-

Journal of Powder Materials 2025;32(6):481-491.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4150/jpm.2025.00465

Published online: December 31, 2025

1Department of Materials Science and Engineering, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, 53706, USA

2Korea Institute of Limestone and Advanced Materials, Danyang-gun, Chungcheongbuk-do, 27000, Republic of Korea

- *Corresponding author: Jin-Kyeom Kim E-mail: jkim2288@wisc.edu

© The Korean Powder Metallurgy & Materials Institute

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 814 Views

- 4 Download

Abstract

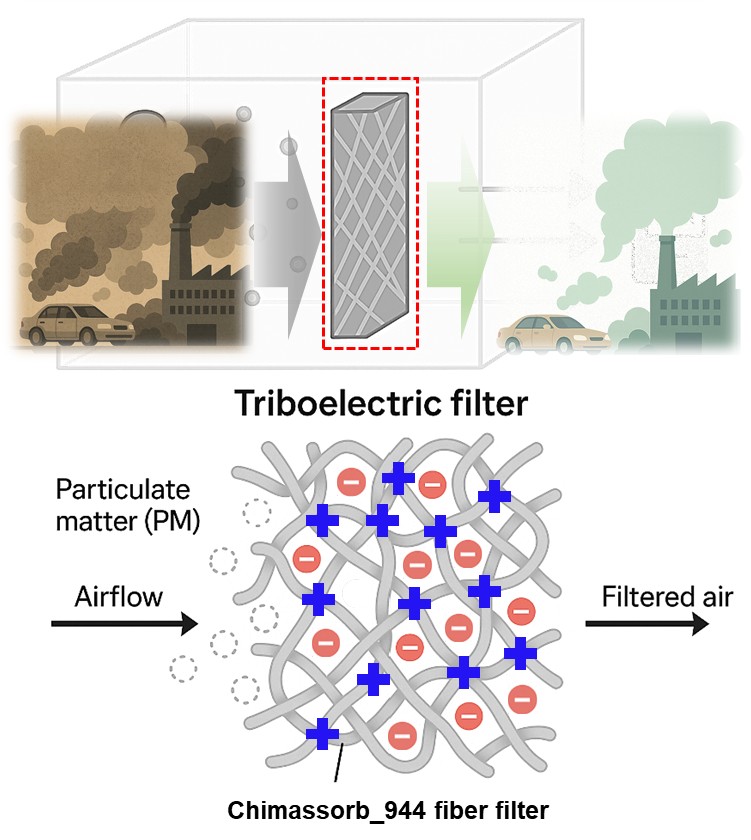

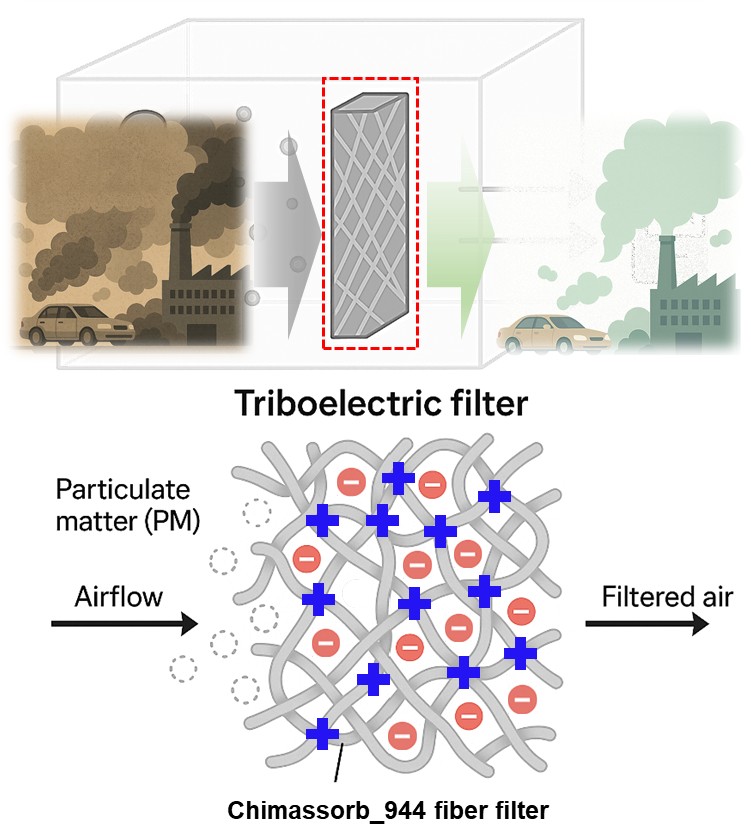

- Particulate matter (PM) pollution demands air filters that combine high efficiency with low pressure drop. Here, we report a self-powered electrostatic filter based on an electrospun cationic microfiber web of Chimassorb 944 (C-fiber). The C-fiber functions as a triboelectric nanogenerator (TENG), generating a surface charge density of 85.8 μC/m2 when paired with polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), which creates a strong electrostatic field for capturing sub-micron particles, including the most penetrating particle size (MPPS). As a result, the triboelectrically charged C-fiber filter maintains >80% filtration efficiency at a high wind speed of 60 cm/s, far exceeding uncharged mechanical filters (<20%) while retaining low air resistance. Kelvin probe force microscopy (KPFM) visualizes the surface-potential change after particle capture, and the gradual decay of TENG output provides a built-in indicator of dust loading. This strategy offers a promising platform for next-generation smart air purification systems.

- In recent years, global concern regarding air quality has intensified due to rapid industrialization and urbanization. Airborne particulate matter (PM), particularly fine particles such as PM2.5 and PM10, has emerged as one of the most pressing environmental and public health concerns worldwide [1, 2]. Prolonged exposure to these pollutants has been linked to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, necessitating the development of efficient air-filtration systems. In response, electrostatic filters have gained significant attention due to their high capture efficiency, low pressure drop, and lightweight nature compared with conventional mechanical filters. Especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, the demand for reliable, high-performance filters capable of blocking pathogens and particulate matter has rapidly increased [3, 4]. Consequently, developing high-performance air filtration systems that can simultaneously block fine dust and deactivate pathogens is of paramount importance.

- Electrostatic filters, which rely on stored charges to attract and capture airborne particulates, are widely employed in air purification and protective mask applications [5, 6]. However, their performance is often limited by insufficient charge density, rapid charge dissipation under high humidity conditions, and reliance on charging methods such as corona discharge, which suffer from poor long-term stability. In addition, conventional filters primarily target fine dust particles, while offering little resistance to microbial contamination, thereby limiting their multifunctionality in real-world environments. Another emerging requirement in filtration technology is the incorporation of antibacterial properties [7, 8]. Filters not only serve as barriers against particulate matter but also as potential breeding grounds for harmful microorganisms. To address this, recent research has investigated the introduction of functional nanoparticles, including silicon- and iron-based materials, which can provide intrinsic antibacterial activity [9, 10]. Despite their promising potential, the systematic study of their mechanisms and their integration into nanocomposite fiber systems is still at an early stage.

- Recently, triboelectric nanogenerators (TENGs), which utilize the fundamental principles of contact electrification and electrostatic induction, have attracted significant attention in the fields of energy harvesting, sensing, and air purification [11, 12]. When two dissimilar materials come into contact and subsequently separate, a potential difference is established due to differences in electron affinity, allowing generation and accumulation of surface charges [13, 14]. This unique mechanism enables TENGs to efficiently convert ambient mechanical stimuli into electrostatic energy without the need for an external power source [15-17]. Importantly, the sensitivity of TENGs to environmental forces and their ability to continuously regenerate charges provide an attractive opportunity for improving electrostatic filter technologies [18, 19]. Electrostatic filtration is typically achieved through two primary mechanisms: triboelectric charging and external charging methods such as corona [20-22]. Consequently, there is a strong need for new materials and structures that can simultaneously improve charge density, maintain electrostatic stability, and offer mechanical adaptability.

- Electrospinning provides an attractive route to fabricate fibrous filter media that simultaneously satisfy the structural and electrical requirements of next-generation electrostatic filters [23, 24]. This technique enables the formation of highly porous microfibrous webs with tunable fiber diameter, pore size, and thickness, which are essential for balancing high particulate capture efficiency with low pressure drop [25]. The resulting three-dimensional network offers a large specific surface area and interconnected pathways that facilitate efficient interception of fine particles while maintaining good air permeability [26, 27]. In addition, electrospun fibers exhibit excellent mechanical flexibility and conformability, allowing intimate contact and repeated deformation under small pressure or airflow fluctuations—conditions that are highly favorable for triboelectric charge generation [28, 29]. When combined with electrostatically active polymers such as hindered amine light stabilizers (HALS), electrospun mats can therefore serve as both efficient filter substrates and high-output TENG layers, enabling in-situ charge generation and sustainable electrostatic filtration without the need for external charging processes [30, 31].

- In this study, we aim to develop advanced electrostatic filters by fabricating microfiber webs through electrospinning of electrostatically active composite materials. By optimizing electrospinning parameters—including applied voltage, collector distance, and solution flow rate—fibers with diameters below 1μm and pore sizes above 2μm will be achieved, ensuring both high filtration efficiency (>90% for PM2.5) and mechanical integrity. To address the shortcomings of the prior art, we developed a filter using a novel microfiber filter medium composed of hindered amine light stabilizer (HALS) polymers, which inherently exhibit stable positive charges [32]. To enhance the electret properties, Chimassorb®944 Poly[[(1,1,3,3-tetramethylbutyl) amino] -1,3,5-triazine-2,4-diyl] [(2,2,6,6- tetramethyl-4-piperidinyl) imino]-1,6-hexanediyl [(2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-4- piperidinyl) imino]]) (CAS No. 71878-19-8 or 70624-18-9) was incorporated into the polymer matrix [33, 34]. Furthermore, the paper provides a novel electrospinning method that successfully manufactures microfibers from the HALS polymer while utilizing the triboelectric effect. This method employs an innovative dual-solvent system that precisely controls interactions between polymer chains and solution properties, thereby delivering high efficiency. The friction-based Chimassorb filter exhibits excellent electrostatic filtration performance without requiring separate external charging processes or complex additives, fundamentally overcoming the limitations of existing technologies.

- This work represents a creative and challenging step toward overcoming the limitations of current electrostatic filter materials. Building on the microfiber platform developed here, future studies will combine in-situ triboelectric charge regeneration with controlled hydrocharging to systematically optimize charge generation and retention under realistic airflow and humidity conditions [35, 36]. In addition, integrating biodegradable flexible polymers (e.g., PLA, PDMS) and antibacterial nanoparticles (e.g., silicon- or iron-based agents) into the electret matrix is expected to impart mechanical adaptability and dual functions of fine particulate removal and bacterial suppression [37]. Together, these efforts will help establish a new class of multifunctional electrostatic filters that couple stable charge storage with enhanced environmental and healthcare compatibility.

1. Introduction

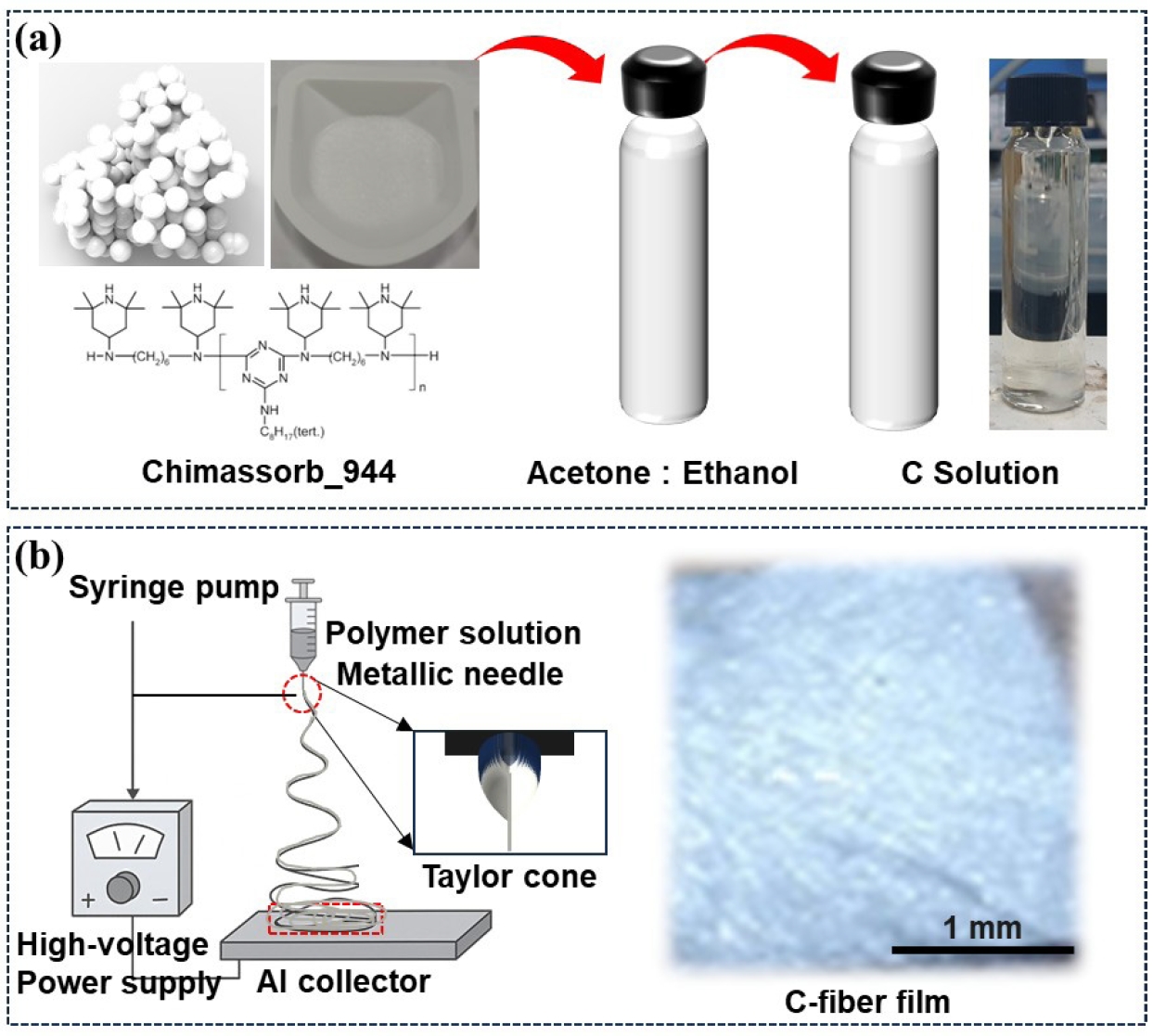

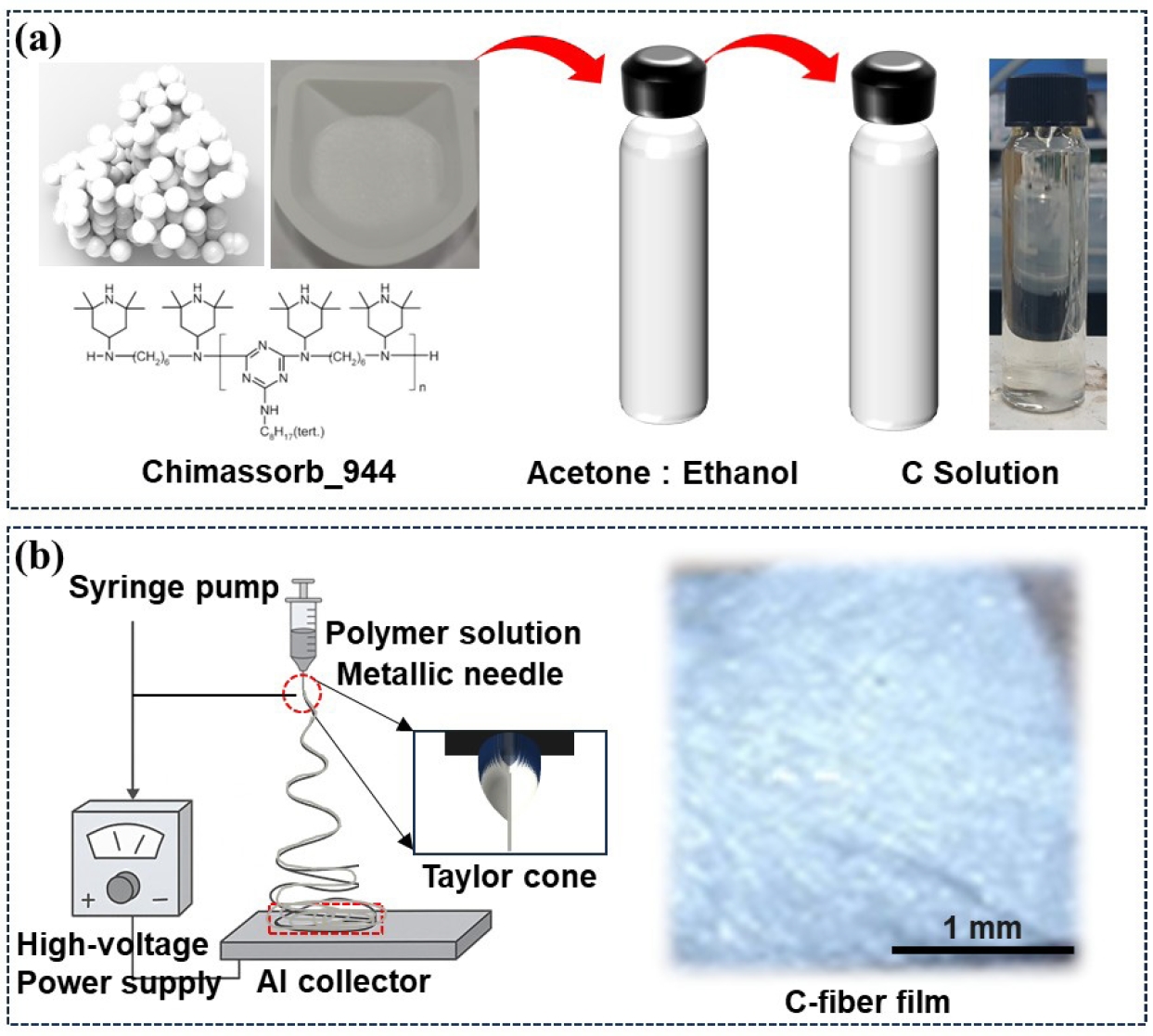

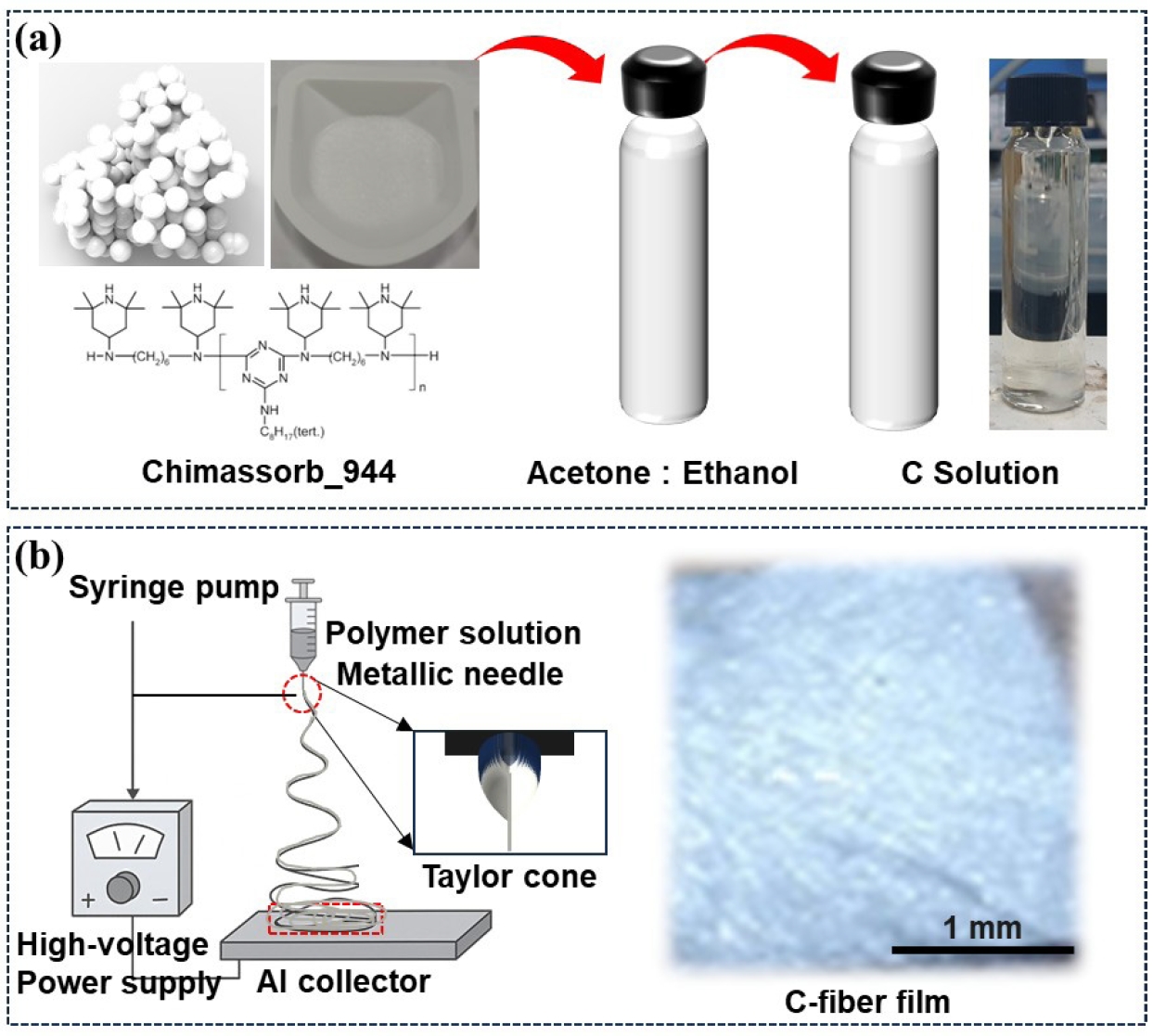

- 2.1 Fabrication of C-fiber Filters

- Weigh 2.50 g of Chimassorb 944 (purchased from Sigma Aldrich) into a 15 mL vial using an electronic balance. Prepare the precursor solution (hereafter referred to as the C-solution) by adding 1.4 mL of acetone and 0.6 mL of ethanol. Acetone serves as the primary good solvent for Chimassorb 944, while the small amount of ethanol acts as a weak co-solvent that adjusts the viscosity and surface tension of the solution, thereby promoting stable jet formation during electrospinning. After adding the solvents, seal the vial tightly with parafilm and place it in an ultrasonic bath for 2 h to obtain a homogeneous and transparent solution without visible precipitation. The C-solution is then transferred to a 10 mL syringe equipped with a 26-gauge needle and mounted on the electrospinning apparatus. The flow rate, tip-to-collector distance, and applied voltage are set to 3 mL/h, 15 cm, and 8.5 kV, respectively. The collector stage is programmed to move 10 cm in both the x and y directions to ensure uniform deposition of the fibers. Once all parameters are set, electrospinning is initiated and the Chimassorb 944-based microfiber filter is collected for 10–20 min. The as-spun C-fiber mat is subsequently annealed on a hot plate at 60 °C for 20 min to remove residual solvent and to stabilize the fiber morphology.

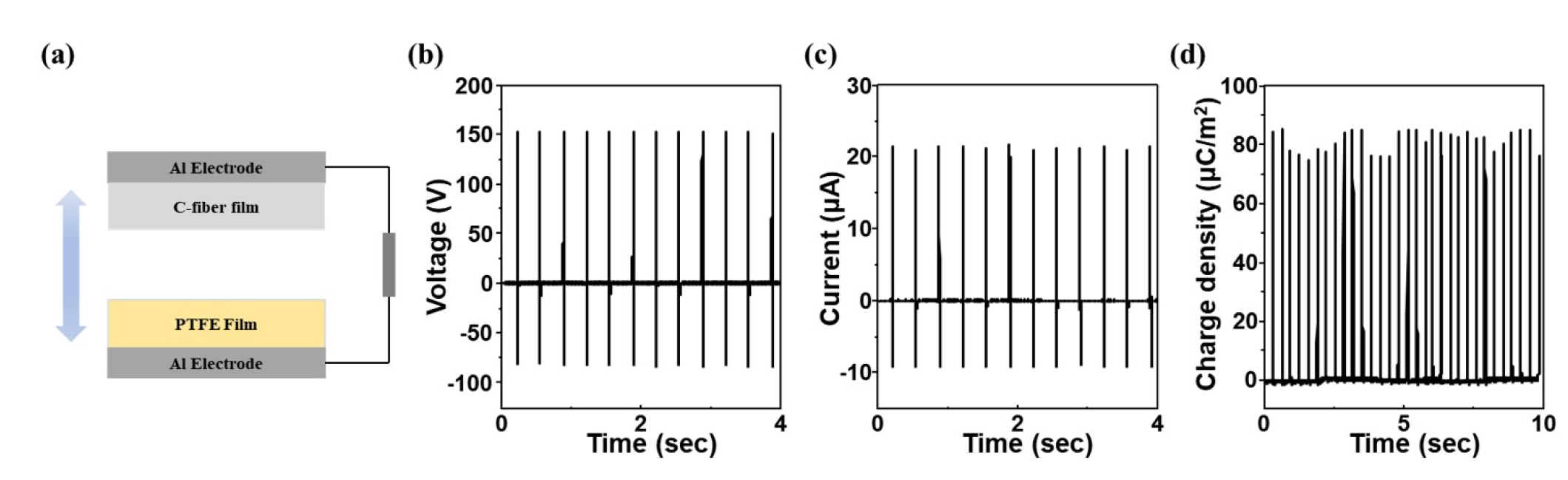

- 2.2 Fabrication of C-fiber Filters Based on TENG

- To fabricate a TENG using a C-fiber layer, the device is fabricated using an Al electrode. The C-fiber layer was attached to the framework for cationic (positively charged) material. The framework of the TENG with dimensions of 4 × 4 cm2 was fabricated using an FDM based 3D printer (Replicator Z18, MakerBot Industries, LLC) with an ABS filament. To fabricate the TENG, the spacer between the C-fiber layer and the PTFE (Polytetrafluoroethylene) film on the electrode, which acts as the top electrode and negatively charged material, was fabricated using four springs with lengths of 5 mm in each corner. Finally, the C-fiber-based TENG was obtained. The active area and gap distance of the TENGs were 2 × 2 cm2 and 1 mm, respectively.

- 2.3 The PM Filtration Efficiency performance of C-fiber

- The filtration performance of the fabricated C-fiber filter was evaluated using a custom-designed experimental setup housed in a transparent acrylic chamber to visualize the process. An electric fan was positioned at the inlet of the chamber to generate a controllable airflow, directing the polluted air towards the filter medium. To simulate a severe air pollution environment, PM was generated by burning incense, which is known to produce particles primarily in the size range of 0.05 to 1.0 μm, with a median diameter of approximately 0.3 μm. This size range covers the Most Penetrating Particle Size (MPPS), making it suitable for evaluating the filtration efficiency against fine and ultrafine particles. The burning incense was placed upstream, allowing the generated smoke to mix with the airflow before reaching the filter. It was tightly sealed in the central holder of the chamber to prevent any air leakage around the edges. The concentration of particulate matter passing through the filter (downstream concentration) was continuously monitored using a portable PM detector over a fixed period. The filtration efficiency was then calculated by comparing the PM concentrations before and after filtration. The pressure drop (ΔP) across the filter was measured as the static differential pressure between the upstream and downstream sides using a digital differential pressure manometer (range: 0–500 Pa; resolution: 1 Pa). To prevent bypass leakage, the filter was mounted in a sealed standard 47 mm holder with an effective filtration area of approximately 14.6 cm2. Pressure taps were positioned roughly 5 cm upstream and 5 cm downstream of the filter media. For each face velocity (10–60 cm/s), the airflow was allowed to stabilize for 30 s, after which ΔP was recorded for 60 sec at a sampling rate of 1 Hz. The reported ΔP values represent the time-averaged results, from which the baseline pressure drop of the empty holder was subtracted. All measurements were performed in triplicate using independent mountings, and the results are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

- 2.4 Characterization and Measurements

- The surface morphology of the C-fiber layers was examined using Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FE-SEM). To evaluate the electrical performance of the TENGs, the output voltage and short-circuit current were recorded using a digital phosphor oscilloscope (DPO 3052, Tektronix) coupled with low-noise preamplifiers (SR560 for voltage and SR570 for current, Stanford Research Systems, Inc.). Charge density was quantified using a Keithley 6514 system electrometer. For the optimization of output charge density, the samples were subjected to consistent contact-separation cycles (force: 30 N, frequency: 3 Hz) for 10 minutes prior to measurement. Kelvin probe force microscopy (KPFM) images (3 × 3 μm2) were scanned at a scanning speed of 0.3 Hz. KPFM measurements were carried out with a 2 VAC signal and a frequency of 17 kHz. Measurement proceeds with the electrostatic force microscopy (EFM) method which measures the potential in non-contact mode. KPFM measurements were carried out with a 2 VAC bias amplitude with a resonance frequency of 17 kHz. After measuring the surface potential of the sample, consistent filtering time was applied to the samples using a filter system to obtain data on the change in surface potential value.

2. Experimental

- 3.1 Fabrication of Chimassorb 944-based Microfiber Web

- The fabrication process of the electrostatic C-fiber film is systematically illustrated in Fig. 1. As the primary electret material, Chimassorb 944 (poly[[6-[(1,1,3,3-tetramethylbutyl)amino]-1,3,5-triazine-2,4-diyl][(2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-4-piperidinyl)imino]-1,6-hexanediyl[(2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-4-piperidinyl)imino]]) was selected due to its excellent charge storage capability and thermal stability. Fig. 1(a) depicts the preparation of the precursor solution. The Chimassorb 944 granules were dissolved in a binary solvent system consisting of acetone and ethanol. This solvent combination was chosen to ensure optimal volatility and solubility, which are critical for stable jet formation during electrospinning. The mixture was stirred until a homogeneous and transparent solution (referred to as C-solution) was obtained, confirming the complete dissolution of the polymer without any visible precipitation. Detailed information on creating fiber can be found in the experimental section.

- Subsequently, the C-solution was processed into a nonwoven microfiber web via the electrospinning technique, as shown in Fig. 1(b). A high-voltage power supply was connected to the metallic needle to generate a strong electric field. When the electrostatic repulsive force overcame the surface tension of the polymer droplet at the needle tip, a Taylor cone was formed, ejecting a charged fluid jet towards the grounded aluminum collector. As the solvent evaporated during the flight, solid microfibers were randomly deposited, forming a porous web. The optical photograph in Fig. 1b shows the as-fabricated C-fiber film, which exhibits a uniform white appearance, indicating the successful formation of a defect-free microfiber layer.

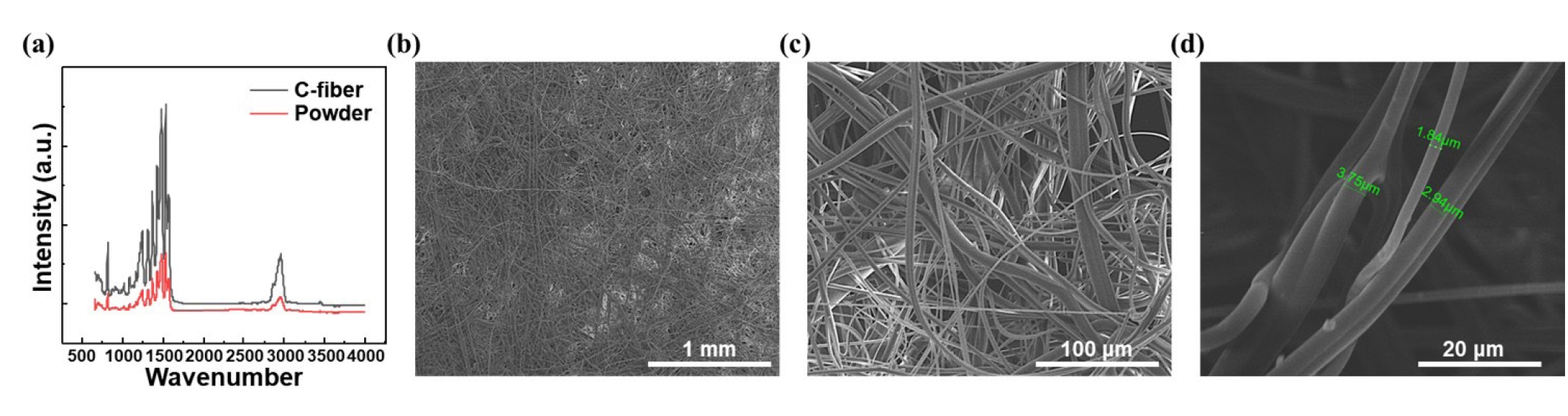

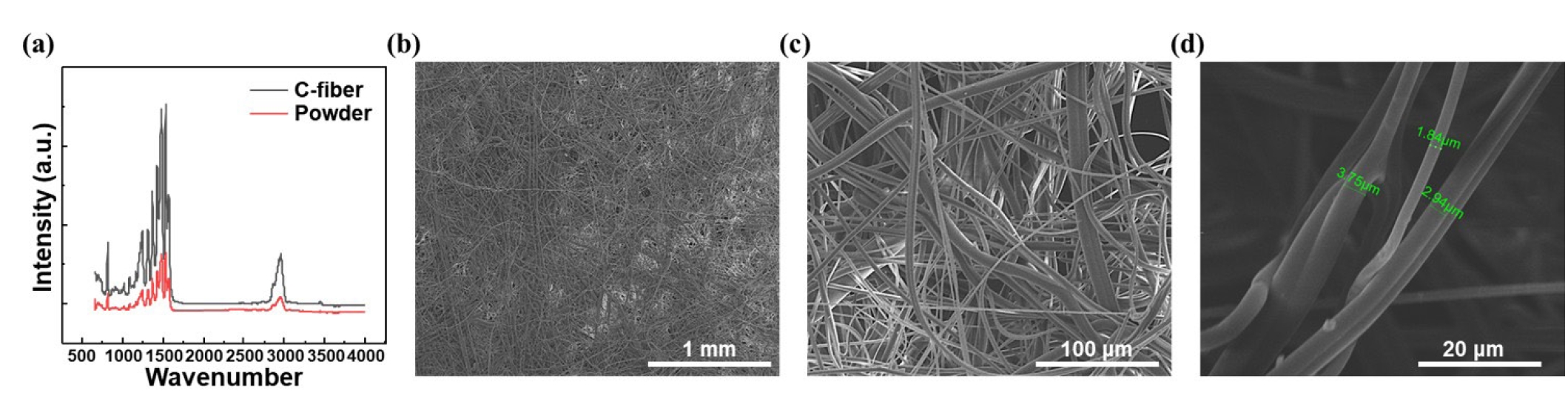

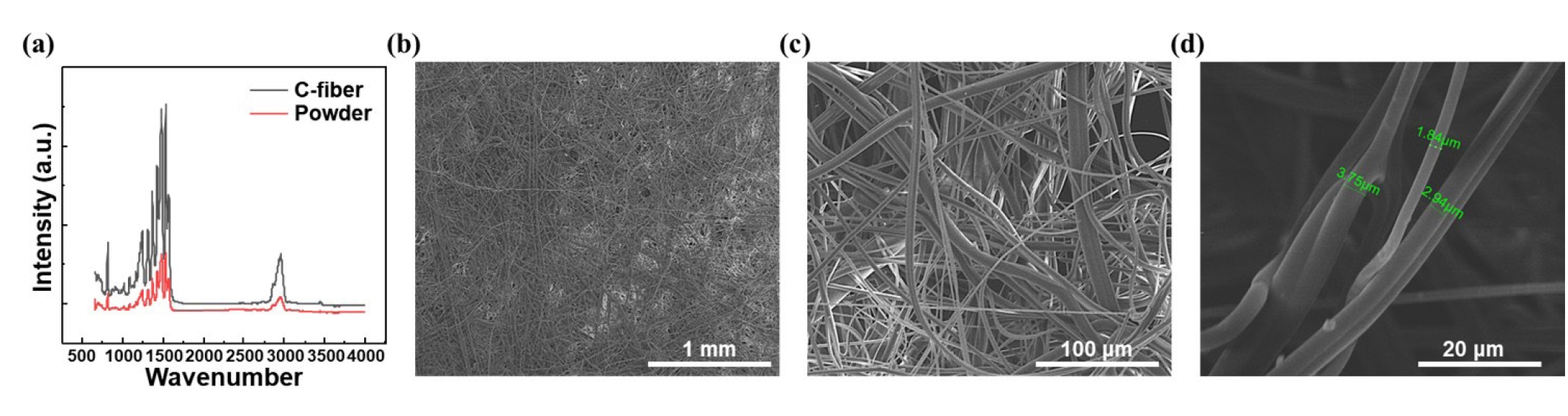

- 3.2 Characterization of Chimassorb 944 Fiber Web

- The chemical and morphological properties of the electrospun Chimassorb 944 fiber (C-fiber) web were systematically characterized to verify the material integrity and structural quality after the fabrication process. Fig. 2(a) presents the comparative FT-IR spectra of the raw Chimassorb 944 powder and the electrospun C-fiber. As observed, the characteristic peaks of the C-fiber align perfectly with those of the pristine powder. The peaks in the range of 2800-3000 cm-1, corresponding to C-H stretching vibrations, and the fingerprint region (1000-1600 cm-1) associated with C-N bonds and triazine rings, remain unchanged. This identical spectral fingerprint indicates that the electrospinning process is purely physical and that the solvent dissolution and high-voltage application did not induce any chemical degradation or structural alteration in the Chimassorb 944 polymer matrix. This chemical stability is crucial for maintaining the inherent charge-storage capability of the material. The morphological features of the C-fiber web were examined using Field-Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FE-SEM) at various magnifications, as shown in Fig. 2(b–d). The low-magnification images (Fig. 2(b) and 2(c)) reveal that the fibers are randomly oriented, forming a highly porous non-woven network. This interconnected porous structure is advantageous for air filtration applications, as it provides tortuous paths for physical interception of particulate matter while maintaining air permeability (breathability). High-magnification analysis (Fig. 2(d)) further confirms the quality of the fibers. The fibers exhibit a smooth surface morphology without the formation of beads or structural defects, suggesting that the concentration of the precursor solution and the electrospinning parameters (voltage, flow rate, and distance) were well-optimized. The fiber diameters were measured to be in the range of approximately 1.8 to 3.8μm. The formation of defect-free microfibers with a high surface-to-volume ratio is expected to enhance the contact area for triboelectric charging and maximize filtration efficiency.

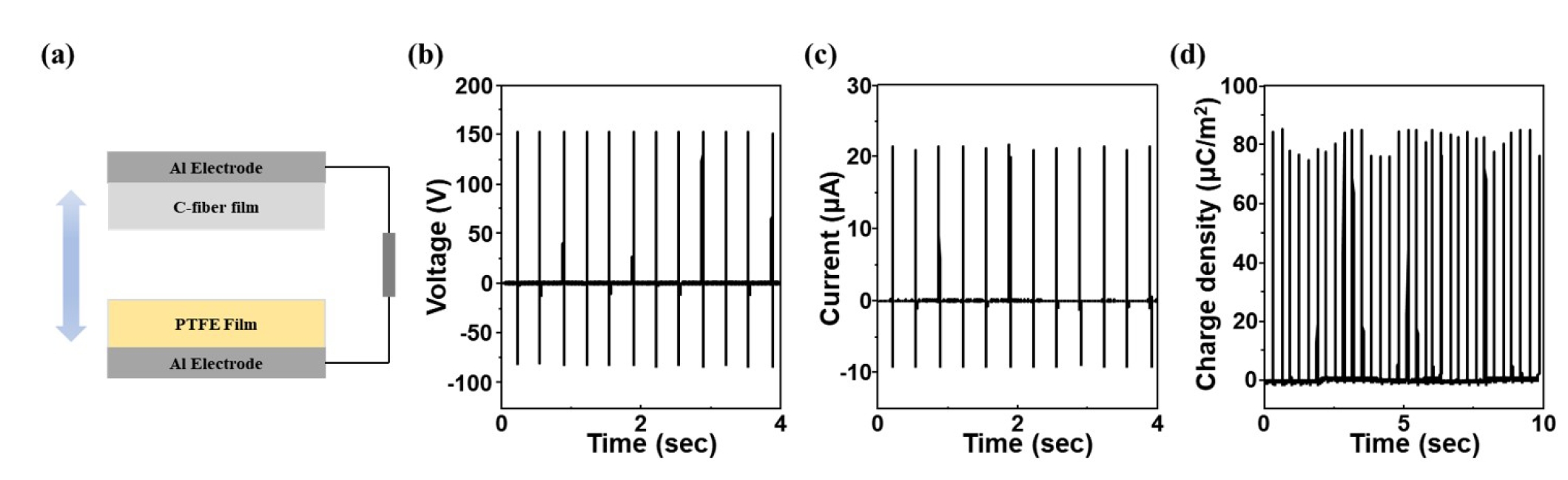

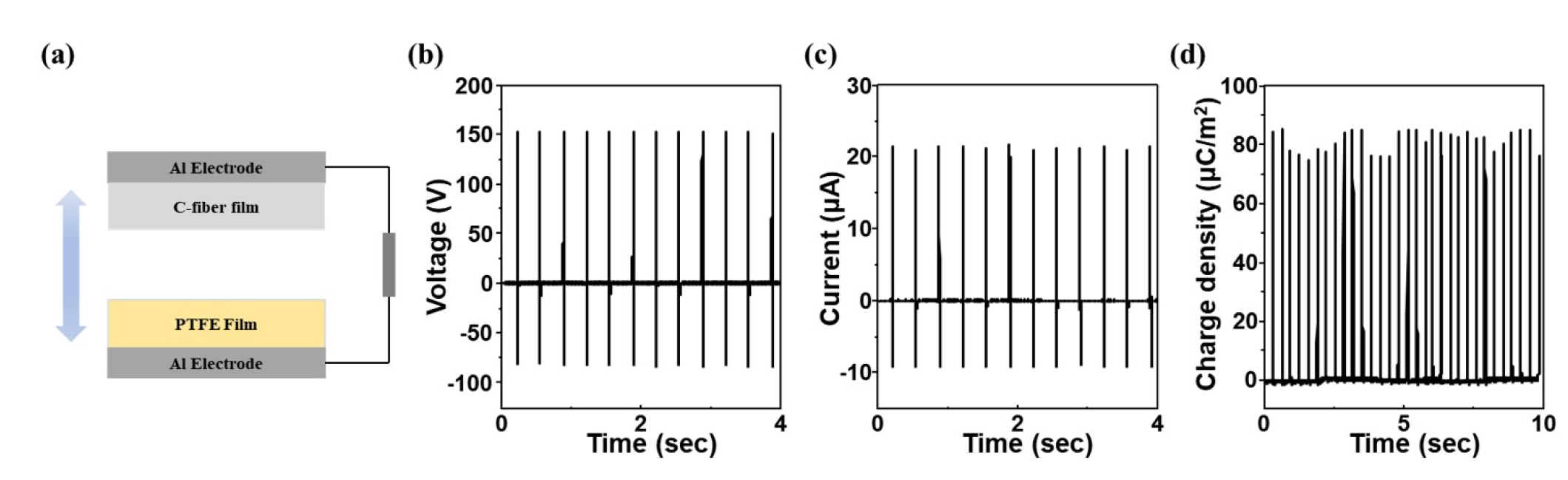

- 3.3 Triboelectric Output Performance of C-fiber-based TENG

- To quantitatively evaluate the electrostatic induction capability and the charge-donating tendency of the fabricated C-fiber web, a vertical contact-separation mode TENG was constructed. Fig. 3(a) illustrates the schematic diagram of the device, where the C-fiber film serves as the triboelectric positive layer and a PTFE film serves as the negative counterpart. Aluminum (Al) foils were attached to the back of both layers to function as electrodes. The electrical output performance was measured under a periodic vertical compressive force of 30 N at a frequency of 3 Hz. Fig. 3(b) and 3(c) display the open-circuit voltage Voc and short-circuit current Isc of the C-fiber TENG, respectively. The device generated a high peak-to-peak voltage of approximately 154 V and a peak current of 24.6 μA. The stability and uniformity of the output signals over repeated cycles indicate the mechanical durability and reliable charge generation capability of the C-fiber web. Crucially, the transferred charge density(σ), which is the most critical factor determining the efficiency of electrostatic filtration, was calculated and plotted in Fig. 3(d). The C-fiber TENG exhibited a remarkable surface charge density of approximately 85.8 μC/m2. This high output performance is attributed to two main factors. One is the intrinsic material property of Chimassorb 944 contains abundant hindered amine groups, which have a strong tendency to lose electrons (strong triboelectric positivity) when contacting electronegative materials like PTFE. The second factor is the morphological advantage. As confirmed by the SEM images, the microfibrous structure provides a significantly larger effective contact area compared to a flat film, facilitating more extensive charge transfer during contact electrification. Consequently, the high surface potential generated by the C-fiber web suggests that it can form a strong electric field around the fibers, which is essential for capturing fine particulate matter via electrostatic attraction.

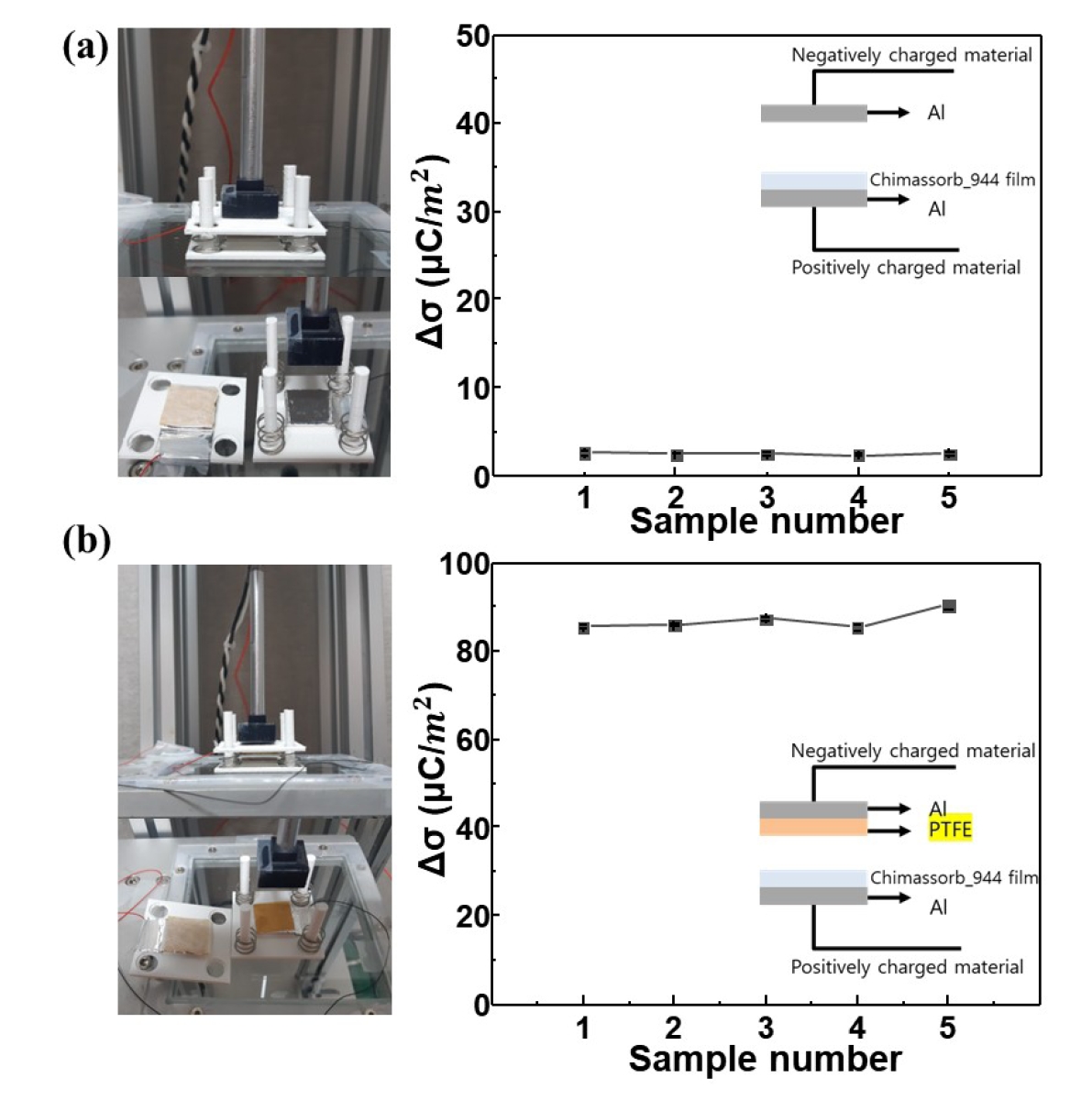

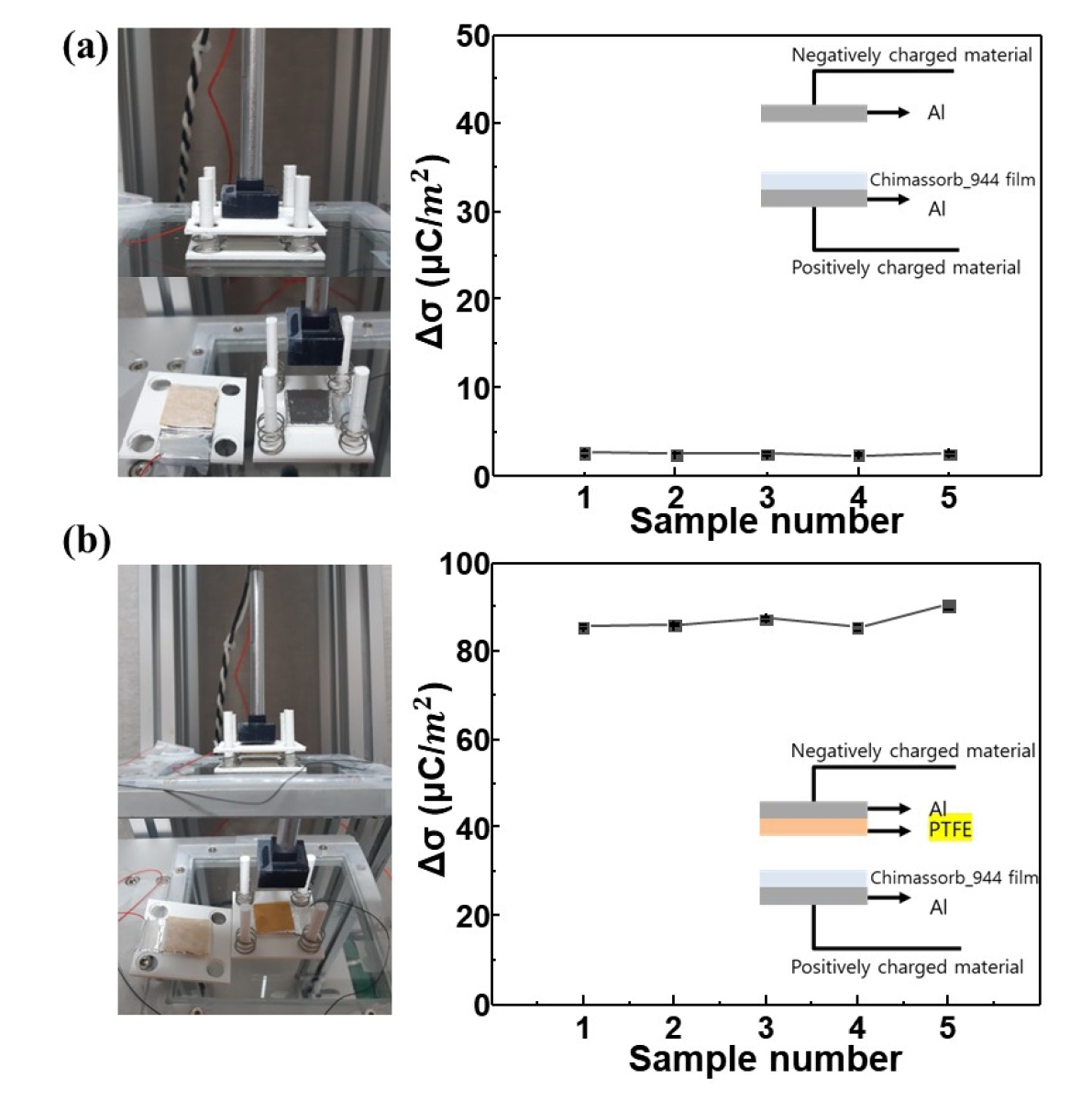

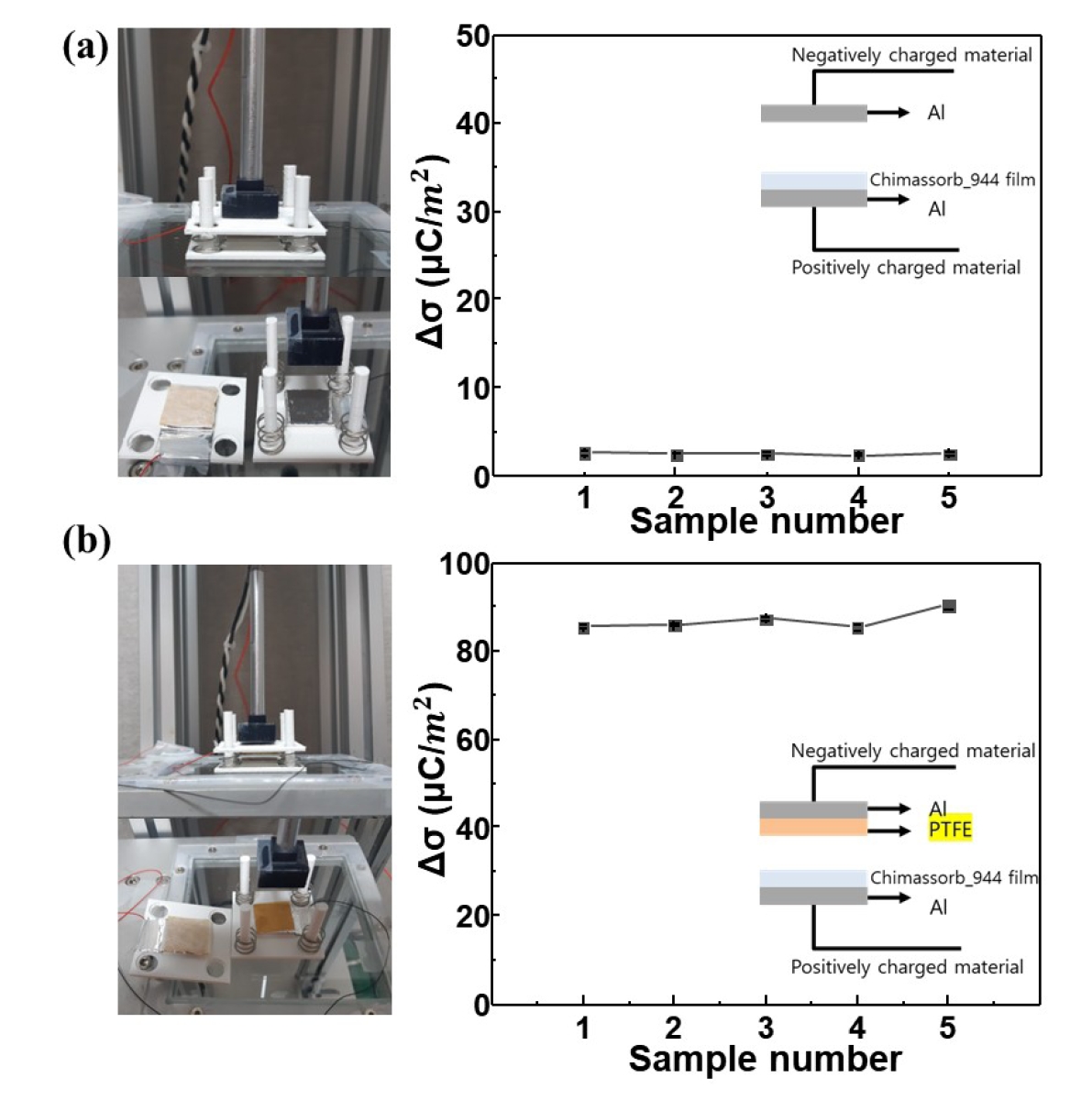

- 3.4 Verification of Triboelectric Polarity and Reproducibility

- To explicitly determine the triboelectric polarity and assess the reliability of the charge generation capability of the C-fiber web, a comparative study was conducted using different counter-triboelectric materials. The results are summarized in Fig. 4. First, to verify the relative polarity, the C-fiber film was paired with Aluminum (Al), which is generally considered a triboelectrically positive or slightly neutral material. As shown in Fig. 4(a), when the C-fiber was contacted with the Al electrode (without PTFE), the generated charge density was negligible, averaging only 2.5 μC/m2. This low output indicates that the difference in electron affinity between the C-fiber and Aluminum is minimal, suggesting that both materials occupy similar positions on the triboelectric series (i.e., the positive side). In stark contrast, when Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), a well-known strongly electronegative material, was used as the contact pair (Fig. 4(b)), the charge density surged dramatically to approximately 85.8 μC/m2. This significant increase—over 30 times higher than the Al-contact case—definitively confirms that the C-fiber possesses a strong tendency to donate electrons, thereby acting as a highly effective triboelectric positive (cationic) material. This aligns well with the chemical nature of Chimassorb 944, which is rich in electron-donating amine groups. Furthermore, to evaluate the device-to-device uniformity, the charge density was measured across five distinct samples (Sample #1 to #5) fabricated under identical conditions. As illustrated in the graphs of Fig. 4, the output performance remained highly consistent with a very narrow standard deviation for both test cases. This high degree of reproducibility demonstrates that the electrospinning process produces a uniform distribution of Chimassorb 944 within the fiber matrix, ensuring reliable electrostatic performance for practical air filtration applications.

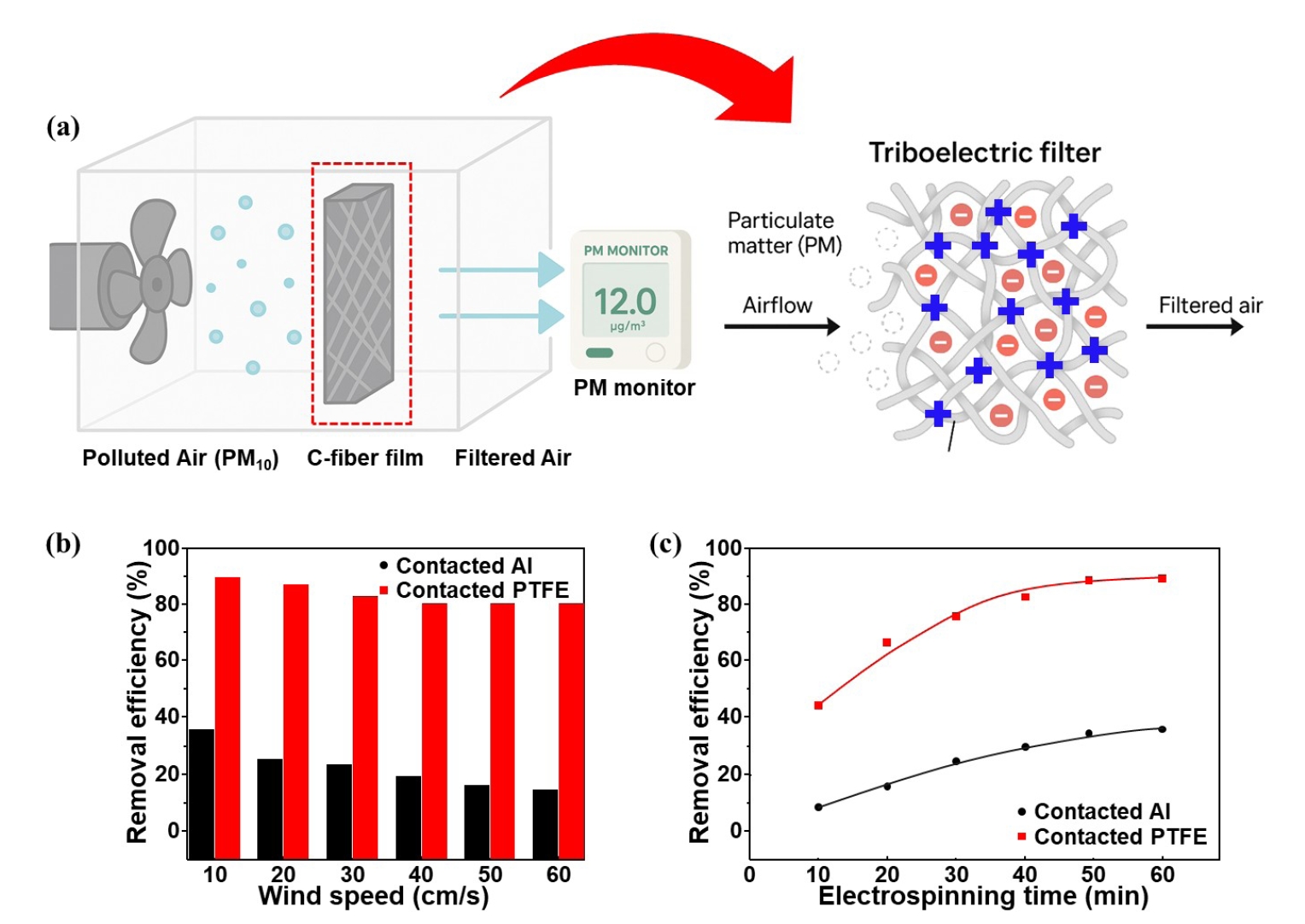

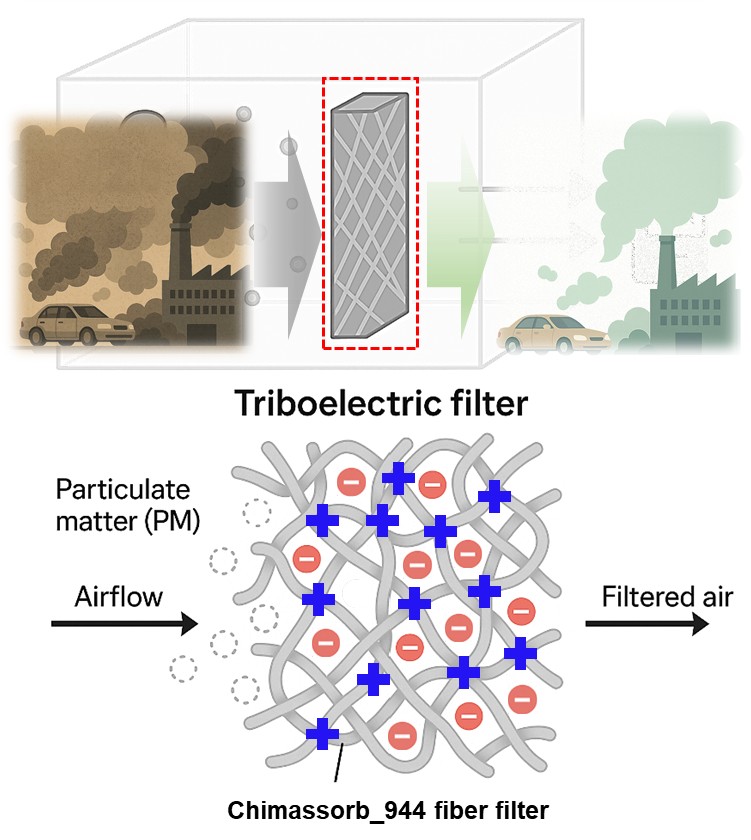

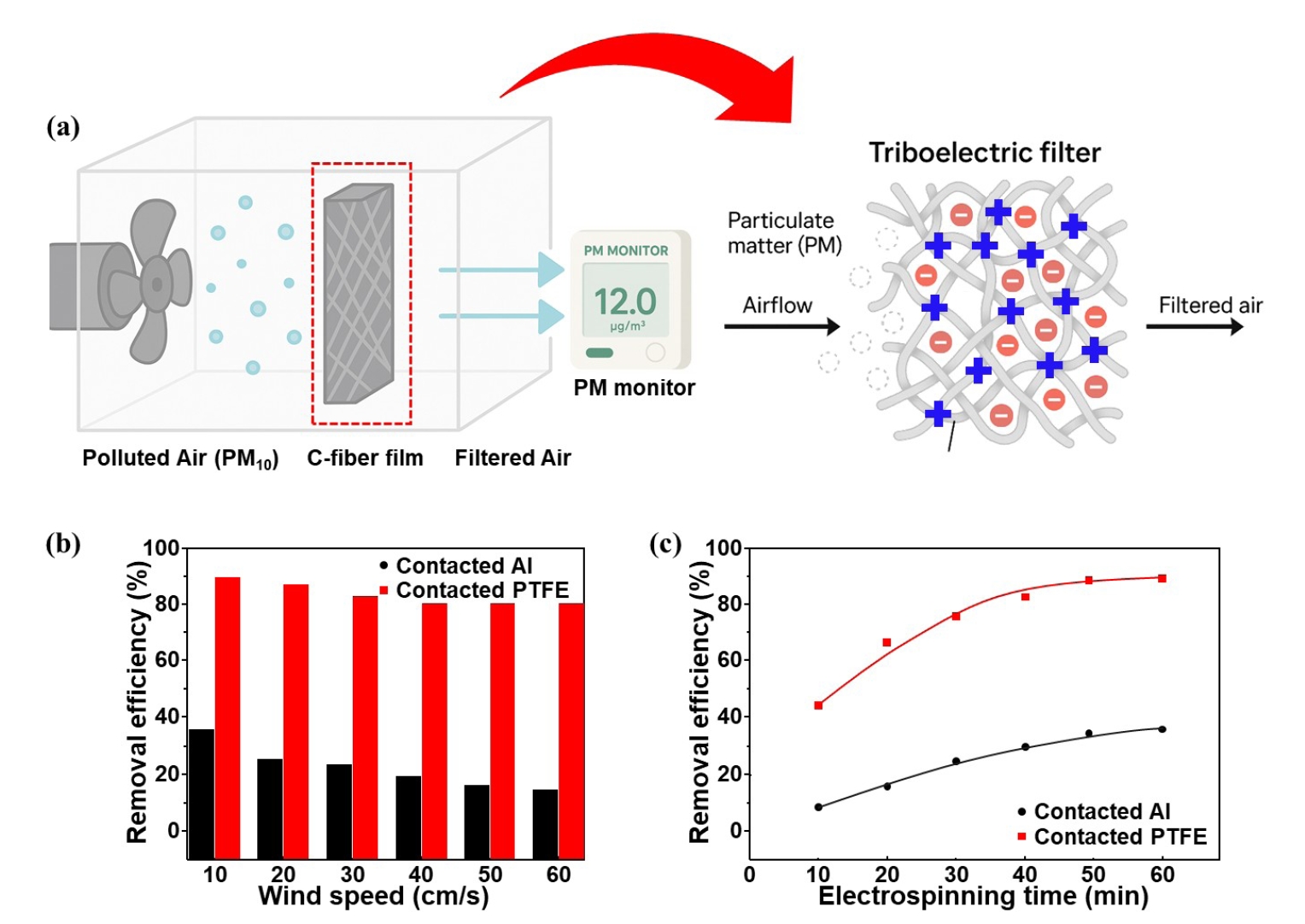

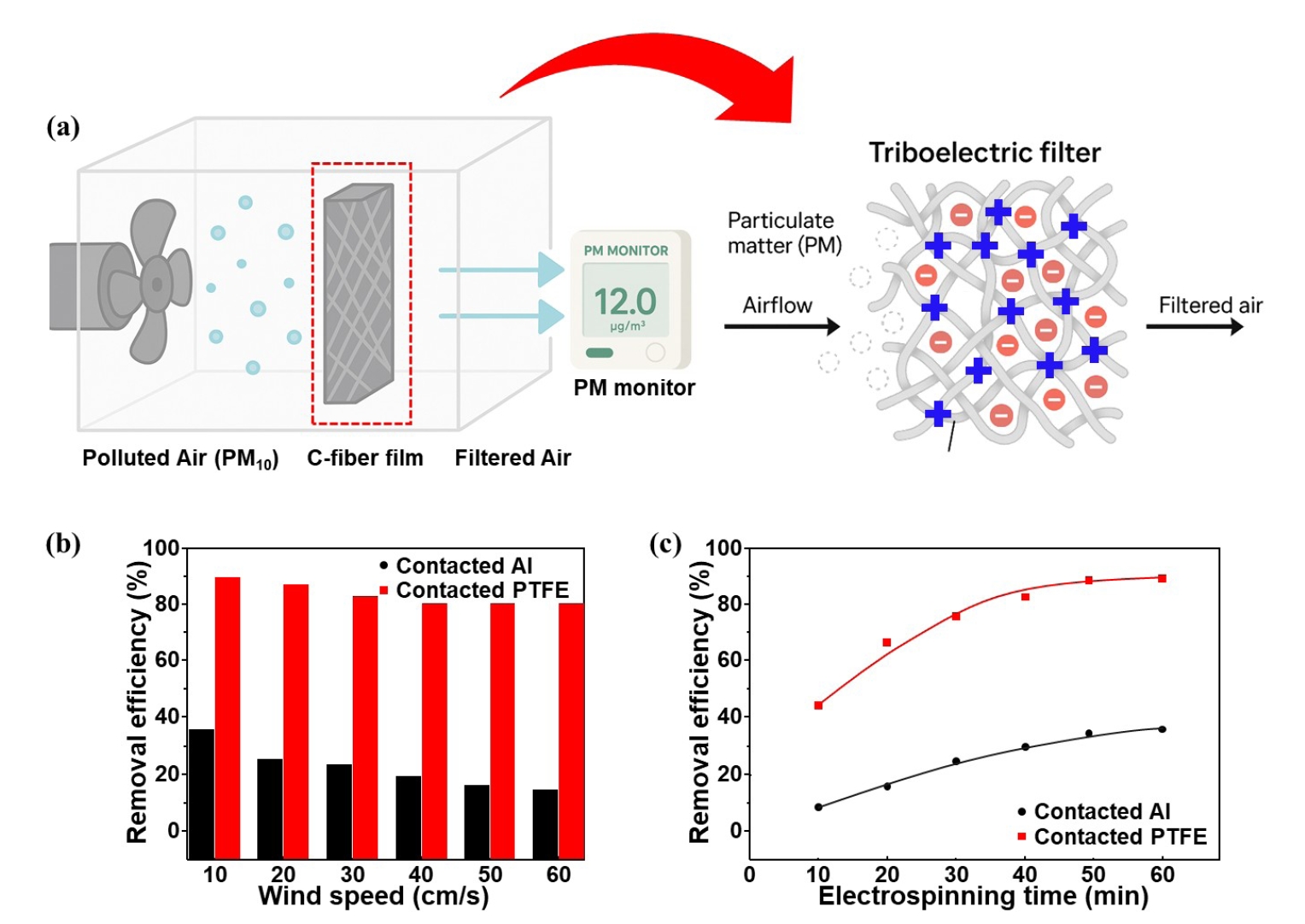

- 3.5 Performance Evaluation of C-fiber-based Electrostatic Filter

- Building upon the confirmed strong cationic nature of the C-fiber web, we investigated its practical application as a high-efficiency particulate matter (PM) filter. Conventional air filters primarily rely on dense fiber networks for physical interception, which inevitably leads to a high-pressure drop and breathing resistance. To overcome this trade-off, this study introduces a triboelectrically charged filtration system. Fig. 5(a) illustrates the filtration mechanism, while physical filters passively block particles, the C-fiber filter, pre-charged via contact with PTFE, actively attracts and captures PM through strong electrostatic forces (Coulomb attraction and dielectrophoresis), effectively targeting both charged and neutral particles in the MPPS range.

- To quantify this enhancement, the removal efficiency was measured under varying wind speeds, as shown in Fig. 5(b). To rigorously quantify the enhanced performance of the C-fiber-based filter, the PM removal efficiency(η) was calculated based on the particle concentrations measured upstream (Cin) and downstream (Cout), as defined by Equation (1).

- Fig. 5(b) presents the comparative removal efficiency under varying wind speeds (ν). Theoretically, the total filtration efficiency (ηtotal) can be expressed as the sum of the contributions from mechanical mechanisms (ηmech) and electrostatic mechanisms (ηelec), as defined by Equation (2) [38].

- For the Al-contacted group (black bars), the electrostatic contribution (ηelec) is negligible, so the filtration relies solely on mechanical mechanisms such as inertial impaction and diffusion (ηtotal ≈ ηmech). As the wind speed increases from 10 to 60 cm/s, the removal efficiency drops to below 20%, because the aerodynamic drag force on the particles overwhelms the weak van der Waals and interception forces, allowing particles to pass through the pores.

- However, for the Contacted PTFE group (red bars), the strong positive surface charge introduces a dominant electrostatic term (ηelec). The charged fibers exert a Coulombic force (FC) and a dielectrophoretic force (FDEP) on the passing particles. Since these electrostatic forces are long-range interactions effective even at higher airflow velocities, the filter maintains a high removal efficiency of over 80% across all measured wind speeds. This experimental result mathematically confirms that the introduction of ηelec via triboelectric charging is critical for high-speed filtration. This robust performance indicates that the electrostatic field generated by the positively charged C-fibers exerts a long-range attractive force, effectively capturing rapidly moving particles that would otherwise penetrate a standard filter.

- Furthermore, Fig. 5(c) highlights the relationship between electrospinning time, which correlates to filter thickness, L and efficiency. In general filtration theory, the Quality Factor (QF), which represents the balance between filtration efficiency and air resistance (pressure drop, ΔP), is defined as Equation (3) [39].

- For the mechanical filter (Contacted Al), increasing efficiency requires a thicker fiber web, longer electrospinning time, which linearly increases the pressure drop (ΔP), resulting in a low QF. In contrast, the triboelectric filter (Contacted PTFE) achieves a high η (> 80%) even at short electrospinning times. This implies that high filtration efficiency can be achieved without a corresponding increase in ΔP. Consequently, the C-fiber TENG filter offers a superior Quality Factor, solving the trade-off between breathability and protection efficiency. This result highlights a critical advantage of the C-fiber TENG filter. It achieves superior filtration efficiency without the need for a thick, dense structure, thereby offering a solution to the classic conflict between high filtration efficiency and low air resistance.

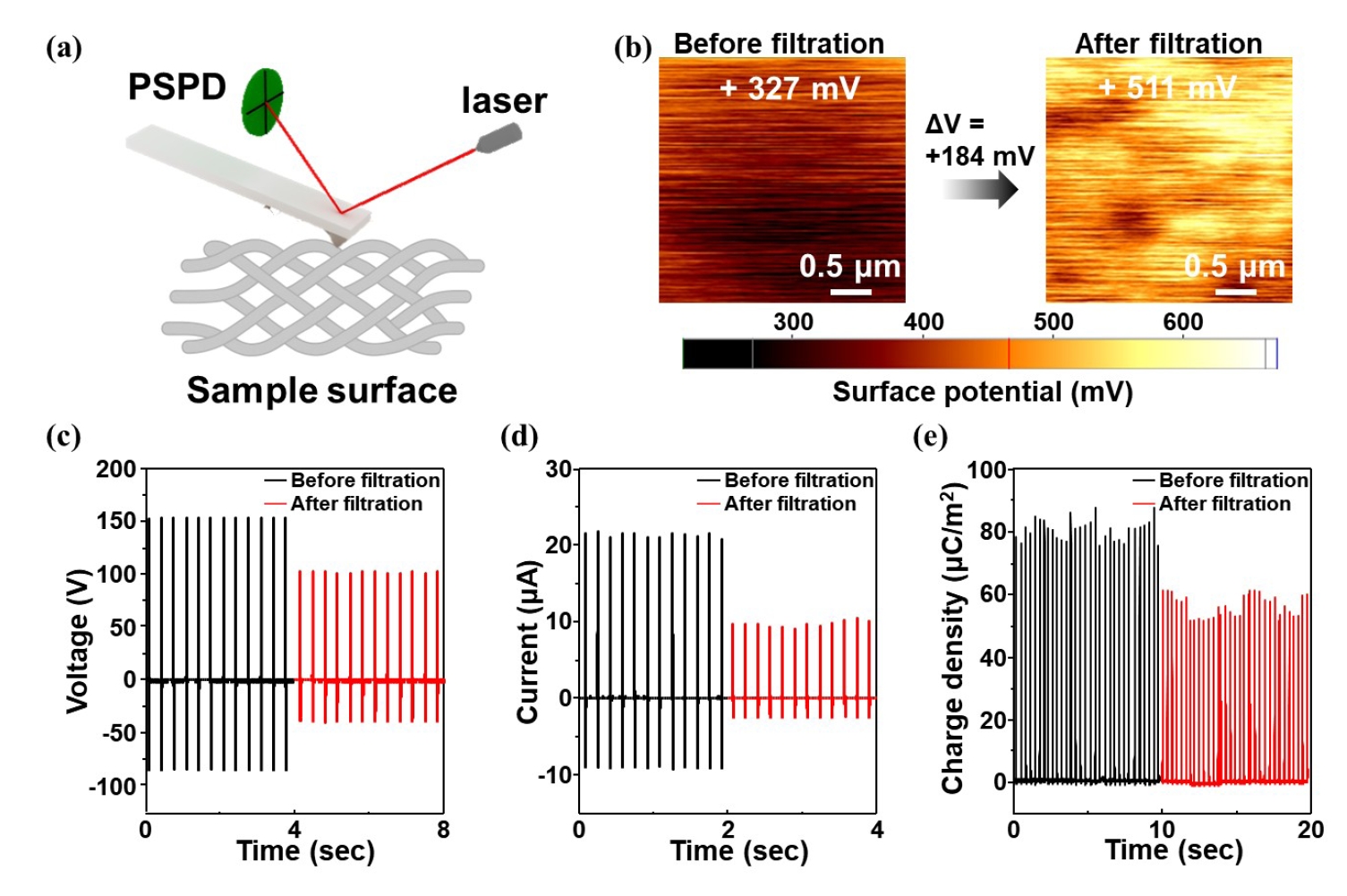

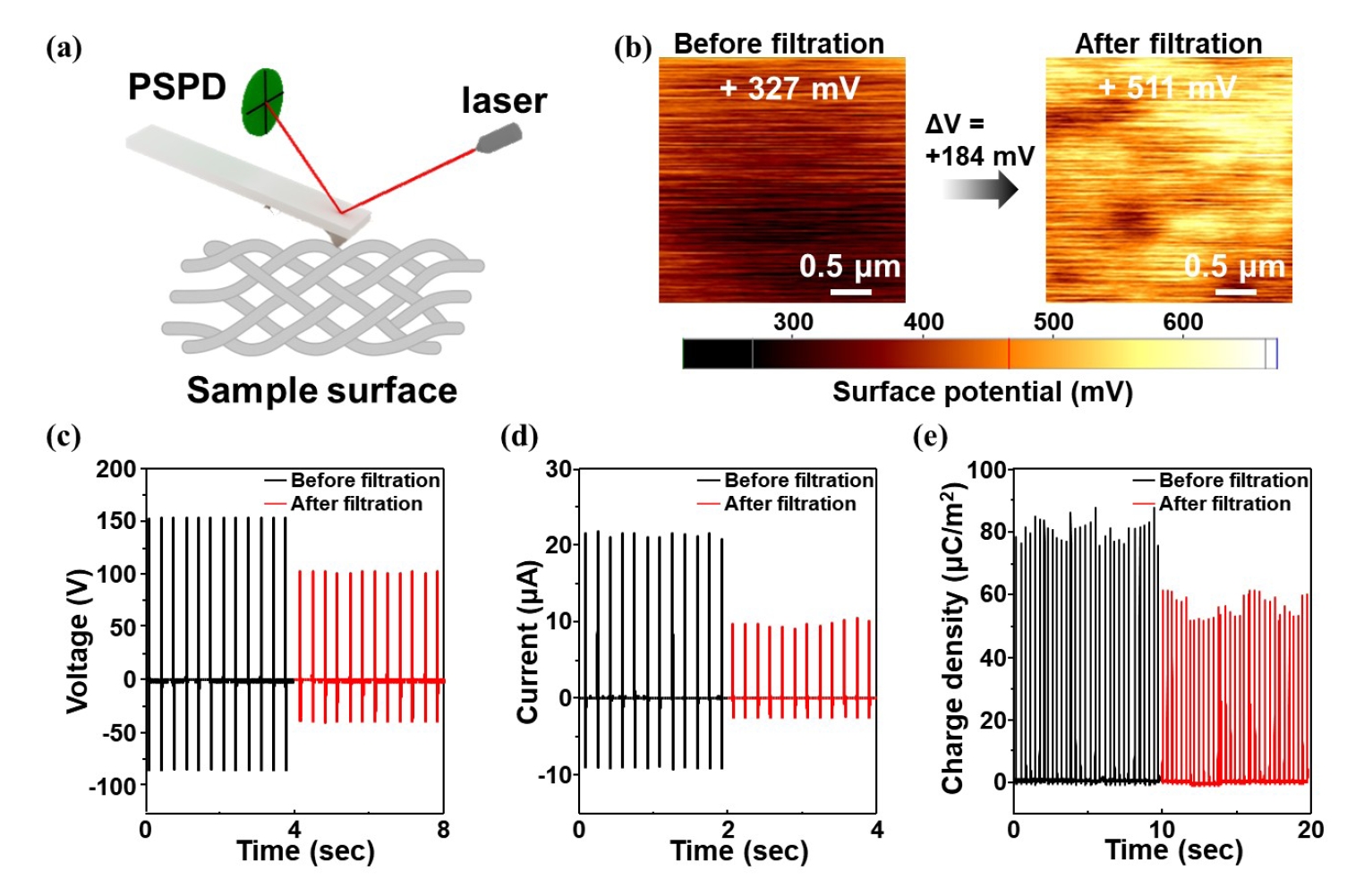

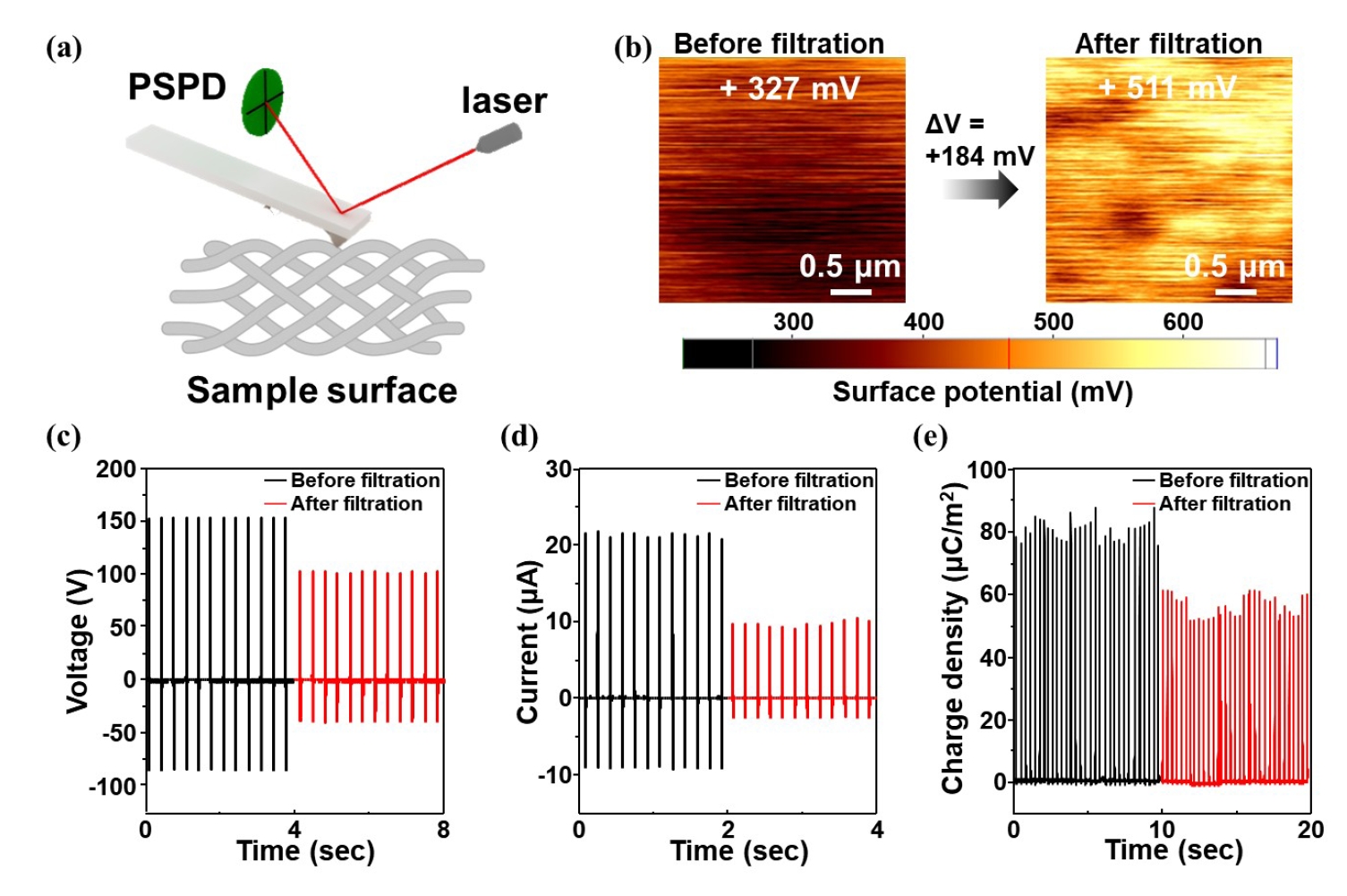

- 3.6 Microscopic and Macroscopic Investigation of Electrostatic Filtration Mechanism

- To provide direct evidence of the electrostatic capture mechanism and to verify the particle adsorption on the fiber surface, we conducted a multiscale investigation using Kelvin probe force microscopy (KPFM) and electrical output measurements, as shown in Fig. 6. Fig. 6(a) illustrates the schematic of the KPFM setup used to map the surface potential distribution of the C-fiber web at the microscale. KPFM is a powerful tool that can visualize the localized electric field generated by the triboelectric charges on the microfibers. Fig. 6(b) presents the comparative surface potential maps before and after the filtration process. Initially, the pristine C-fiber web exhibited a uniform positive surface potential with an average value of approximately +327 mV, confirming its cationic nature. Interestingly, after the filtration process, the surface potential shifted significantly to a higher value of +511 mV. This distinct modulation in surface potential serves as microscopic evidence that the filter successfully captured particulate matter carrying electrical charges (or induced charges), which altered the local surface potential distribution. Also, active interaction is the change in potential confirms that the filtration was not merely a physical sieving process but involved active electrostatic interactions between the fibers and the particles. Complementary to the microscopic KPFM analysis, the macroscopic changes in the TENG output performance were recorded to evaluate the degree of PM accumulation. Fig. 6(c–e) display the Voc, Isc and charge density before and after filtration. Following the filtration process, the electrical output performance exhibited a noticeable decline, attributed to the shielding effect of the captured particulate matter. Specifically, the Voc decreased by approximately 33%, dropping from 154 V to 97 V. Similarly, the Isc showed a substantial reduction of 55% from 24.6 μA to 12.1 μA, while the transferred charge density decreased by about 39% from 85.8 μC/m2 to 52.7 μC/m2. This attenuation in electrical output is attributed to the Shielding Effect caused by the captured dust layer. As PM accumulates on the fiber surface, it reduces the effective contact area and acts as a dielectric barrier, hindering charge induction. The correlation between the KPFM and TENG data underscores the scientific and practical importance of this study. First, the KPFM results visually prove that the C-fiber web maintains a strong electrostatic field capable of interacting with MPPS (Most Penetrating Particle Size), which is the core mechanism for high-efficiency filtration. Second, the TENG output attenuation demonstrates that the C-fiber filter can function as a Self-Powered Smart Filter. By monitoring the decrease in voltage or current in real-time, it is possible to predict the saturation level of the filter and detect the optimal replacement timing without external sensors. This dual functionality high-performance filtration combined with self-monitoring capability presents a significant advancement over conventional passive filters, offering a comprehensive solution for next-generation air purification systems.

3. Results and Discussion

- In this study, we developed a high-performance electrostatic air filter by electrospinning a cationic microfiber web based on Chimassorb 944 (C-fiber). By integrating TENG principles into the filtration architecture, the C-fiber filter alleviates the conventional trade-off between filtration efficiency and air permeability. The fabricated web exhibits a bead-free, uniform microfibrous morphology and excellent chemical stability. In vertical contact–separation mode, the C-fiber shows a strong electron-donating tendency, generating a surface charge density of 85.8 μC/m2 when paired with electronegative PTFE. Filtration tests demonstrate that the triboelectrically charged C-fiber maintains a removal efficiency above 80% for sub-micron particulate matter, even at high wind speeds, whereas the uncharged mechanical filter does not exceed 20%. This superior performance arises from long-range Coulombic attraction and dielectrophoretic forces that effectively capture MPPS without relying on a dense, highly resistive fiber network. Multiscale analysis further clarifies the electrostatic filtration mechanism, KPFM visualizes distinct surface-potential modulation after filtration, and the macroscopic electrical output shows a systematic decay due to the shielding effect of accumulated dust. Together, these features indicate that the C-fiber filter can operate as a self-powered smart sensor for real-time monitoring of filter saturation and replacement timing. Thus, the proposed C-fiber-based triboelectric filter combines high filtration efficiency, low breathing resistance, and self-monitoring capability, offering a promising platform for next-generation air purification and personal protection systems.

4. Conclusion

-

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea(NRF) grant funded by the Korea government(MSIT) (RS-2024-00354872)

-

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

-

Data Availability Statement

The data in this research will be available upon request to corresponding author.

-

Author Information and Contribution

Tae-hyung Kim: Researcher; Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing–original draft.

Jin-Kyeom Kim: PhD, Postdoctoral researcher; Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Data curation, Investigation, Visualization, Writing–original draft, review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Funding acquisition, Project administration.

-

Acknowledgments

None.

Article information

- 1. U. Pöschl and M. Shiraiwa: Chem. Rev., 115 (2015) 4440.Article

- 2. J. E. Thompson: J. Occup. Environ. Med., 60 (2018) 392.Article

- 3. M. H. Chua, W. Cheng, S. S. Goh, J. Kong, B. Li, J. Y. C. Lim, L. Mao, S. Wang, K. Xue, L. Yang, E. Ye, K. Zhang, W. C. D. Cheong, B. H. Tan, Z. Li, B. H. Tan and X. J. Loh: Research, (2020) 7286735.Article

- 4. E. Driggin, M. V. Madhavan, B. Bikdeli, T. Chuich, J. Laracy, G. Biondi-Zoccai, T. S. Brown, C. D. Nigoghossian, D. A. Zidar, J. Haythe, D. Brodie, J. A. Beckman, A. J. Kirtane, G. W. Stone, H. M. Krumholz and S. A. Parikh: J. Am. Coll. Cardiol., 75 (2020) 2352.Article

- 5. A. Marchewicz, A. T. Sobczyk, A. Krupa, L. Sliwinski and A. Jaworek: Powder Technol., 444 (2024) 120062.Article

- 6. A. T. Sobczyk, A. Marchewicz, A. Krupa, L. Sliwinski and A. Jaworek: Fuel, 375 (2024) 132559.Article

- 7. D. Lv, R. Wang, G. Tang, Z. Mou, J. Lei, J. Han, S. De Smedt, R. Xiong and C. Huang: ACS Appl. Mater. Inter., 11 (2019) 35511.Article

- 8. J. Cui, T. Lu, F. Li, Y. Wang, J. Lei, W. Ma, Y. Zou and C. Huang: J. Colloid Interface Sci., 582 (2021) 506.Article

- 9. M. C. Han, S. Z. Cai, J. Wang and H. W. He: Polymers, 14 (2022) 2952.Article

- 10. J. T. Kim, J. Kwon, H. Lee, C. Kim, G. G. Yang, G. S. Lee, C. W. Lee, J. G. Kim, S. Cha, H. T. Jung, S. P. Sasikala and S. O. Kim: ACS Nano, 18 (2024) 6387.ArticlePDF

- 11. D. H. Kim, J. K. Kim, S. Y. Choi, Y. Yang, H. C. Song, H. S. Park, M. Shim and J. M. Baik: Adv. Energy Mater., 14 (2024) 2304012.Article

- 12. J. Oh, J. K. Kim, J. Gao, S. Jung, W. Kim, G. Park, J. Park, J. M. Baik and C. Yang: ACS Nano, 18 (2024).

- 13. J. K. Kim, G. H. Han, S. W. Kim, H. J. Kim, R. Purbia, D. M. Lee, J. K. Kim, H. J. Hwang, H. C. Song, D. Choi, S. W. Kim, Z. L. Wang and J. M. Baik: Energy Environ. Sci., 16 (2023) 598.Article

- 14. S. W. Kim, J. K. Kim, H. J. Kim, C. T. Cao, N. K. Oh, Y. Yang, H. C. Song, M. Shim, H. S. Park and J. M. Baik: Nano Energy, 95 (2022) 107023.Article

- 15. J. K. Kim, S. Jung, D. H. Kim, J. Gao, Y. S. Lee, H. Park, H. C. Song and J. M. Baik: Adv. Energy Mater., 15 (2025) 2304437.Article

- 16. J. K. Kim: J. Electr. Electron. Mater., 38 (2025) 455.Article

- 17. D. W. Hong, W. G. Hong, S.-H. Kim and S.-N. Lee: J. Electr. Electron. Mater., 38 (2025) 107.

- 18. G. M. Rani, C. M. Wu, K. G. Motora, R. Umapathi and C. R. M. Jose: Nano Energy, 108 (2023) 108211.Article

- 19. G. M. Rani, C. M. Wu, K. G. Motora and R. Umapathi: J. Cleaner Prod., 363 (2022) 132532.Article

- 20. J. Chen, S. Gong, T. Gong, X. Yang and H. Guo: Adv. Energy Mater., 13 (2023) 2203689.Article

- 21. K. I. Park: J. Powder Mater., 25 (2018) 263.ArticlePDF

- 22. B. Kim, D. Y. Hyeon and K. I. Park: J. Electr. Electron. Mater., 36 (2023) 525.Article

- 23. J. Xue, T. Wu, Y. Dai and Y. Xia: Chem. Rev., 119 (2019) 5298.Article

- 24. M. A. Bonakdar and D. Rodrigue: Macromol, 4 (2024) 58.Article

- 25. A. A. Koupai, J. Varshosaz, F. Dobakhti, F. Shekarchizadeh, M. H. Al-Musawi, M. M. Kamil, S. H. Turki, H. Valizadeh, F. Sharifianjazi, M. Tavakoli and M. Mirhaj: Int. J. Pharm., 671 (2025) 125231.Article

- 26. S. Shi, Y. Si, Y. Han, T. Wu, M. I. Iqbal, B. Fei, R. K. Y. Li, J. Hu and J. Qu: Adv. Mater., 34 (2022) 2107938.Article

- 27. Z. He, F. Rault, M. Lewandowski, E. Mohsenzadeh and F. Salaun: Polymers, 13 (2021) 174.Article

- 28. Q. Zhu, X. Song, X. Chen, D. Li, X. Tang, J. Chen and Q. Yuan: Nano Energy, 127 (2024) 109741.Article

- 29. X. Ma, N. Sun, Z. Li, M. Tong, Q. Ding, Z. Wang, L. Bai, L. Dong and Y. Liu: Adv. Funct. Mater., 34 (2024) 2312203.Article

- 30. C. Wang, Y. Liu, Z. Jia, W. Zhao and G. Wu: Nano-Micro Lett., 15 (2023.Article

- 31. J. Wang, S. Liu, Z. Chen, T. Shen, Y. Wang, R. Yin, H. Liu, C. Liu and C. Shen: J. Mater. Sci. Technol., 213 (2025) 213.Article

- 32. Y. Zhao, Y. Zhang, J. Ju, Z. Qian, X. Cui, S. Wang, B. Cheng and W. Kang: Sep. Purif. Technol., 332 (2024) 125729.Article

- 33. L. Zhu, Z. Li and K. Hou: High Voltage, 8 (2023) 739.ArticlePDF

- 34. A.R. Jasso, M. L. B. Duarte and N. S. Allen: J. Appl. Polym. Sci., 92 (2004) 280.Article

- 35. H. Zhang, Q. Zeng, N. Liu, H. Xu, X. Zhang, M. Ge, Y. Zhang, W. Zhang, H. Kai and J. Liu: Sep. Purif. Technol., 338 (2024) 126512.Article

- 36. R. Hu, Q. Huang, G. Liu, W. Jiao, Q. Yang, X. Wang, J. Yu and B. Ding: ACS Appl. Polym. Mater., 5 (2023) 4372.ArticlePDF

- 37. Q. Yu, Y. Bai, Z. Li, F. Jiang, R. Luo, Y. Gai, Z. Liu, L. Zhou, Y. Wang, C. Li, K. Ren, D. Luo, H. Meng and Z. Li: Nano Energy, 121 (2024) 109196.Article

- 38. F. Torkan, Z. Yicheng and S. Brent: Indoor Air., 29 (2019) 656.

- 39. H. B. Kim, W. J. Lee, S. C. Choi, K. B. Lee and M. H. Lee: Aerosol Sci. Technol, 55 (2021) 154.Article

References

Figure & Data

References

Citations

Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 6.

Graphical abstract

TOP

KPMI

KPMI

ePub Link

ePub Link Cite this Article

Cite this Article